My Library in the Closet

On the memories triggered by finding one's old books and the need to protect what the arts and ideas we love.

Contrary to my stated purpose, I have failed to post in this newsletter for nearly all of 2024. I did not even complete my promised fourth recap with my publications of 2023, leaving me a pending task of recapping my publications for two years in a future post. It was a tough year. My sabbatical was consumed in finishing a lot of unfinished stuff while dealing with a new puppy with the personality of a hurricane. Then I came back to a Fall semester in which my work time was sucked by having over 150 students with no assistance, while the increasingly bureaucratic structure of the university sucked life and time out of me. I am not completely out of the woods in terms of unfinished stuff—three edited collections in progress and a very advanced monograph will require my attention in 2025. But I think I could at least post some snippets in this newsletter every so often. For starters, in the course of January, I will post once again my favorite books, films and music from last year, and this time I will also publish a couple of recaps on my publications. I thank those who have remained subscribed throughout my radio silence.

What has been in my mind in 2024 is how to exist in intellectual and creative professions during the apocalyptic landscape for humanities and the arts—besieged by the bureaucratization of institutions, anti-intellectualism, the de-emphasis of the institutions that fund us, the deep structural labor crisis and the looming automatization of a lot of our everyday work by the plagiarism and cheating engine called AI. Even being one of the very few who has won what feels like the employment lottery in academia—a puny prize given the state of the humanities in US higher education—, I am at a loss about how to address a lot of these problems head on. But I am committed to the idea, which I already expressed in my essay “The Humanities Are Worth Fighting For,” that a substantive part of the fight must be grounded on thinking about the value of thinking and the arts, a value that cannot be grounded on the institutional “skills” discourse (which AI is now rendering mostly moot) or the surrender of our fields to the STEMification of universities.

This newsletter is not intended to discuss these questions at length. Instead, I have been writing haphazardly a series of essays on the matter that I hope will end on a book about the topic. Rather, I wanted to close this year of frustration and melancholy with a little moment among those that reminded me why I am in this business. One of the quirks of my office at the university comes from having an actual closet with shelves about it. Symbolically in more than one way, one of the oldest, most rundown building of the university houses the language departments (except English, which is in a slightly less rundown neighboring building). But this carries the advantage that you still have relatively large offices that have not fall prey to the cookie cutter minimalism that counterpoints the otherwise ostentatious neoliberal architecture that favors new institutional priorities like business schools and faux creative spaces the few understand how to use exactly.

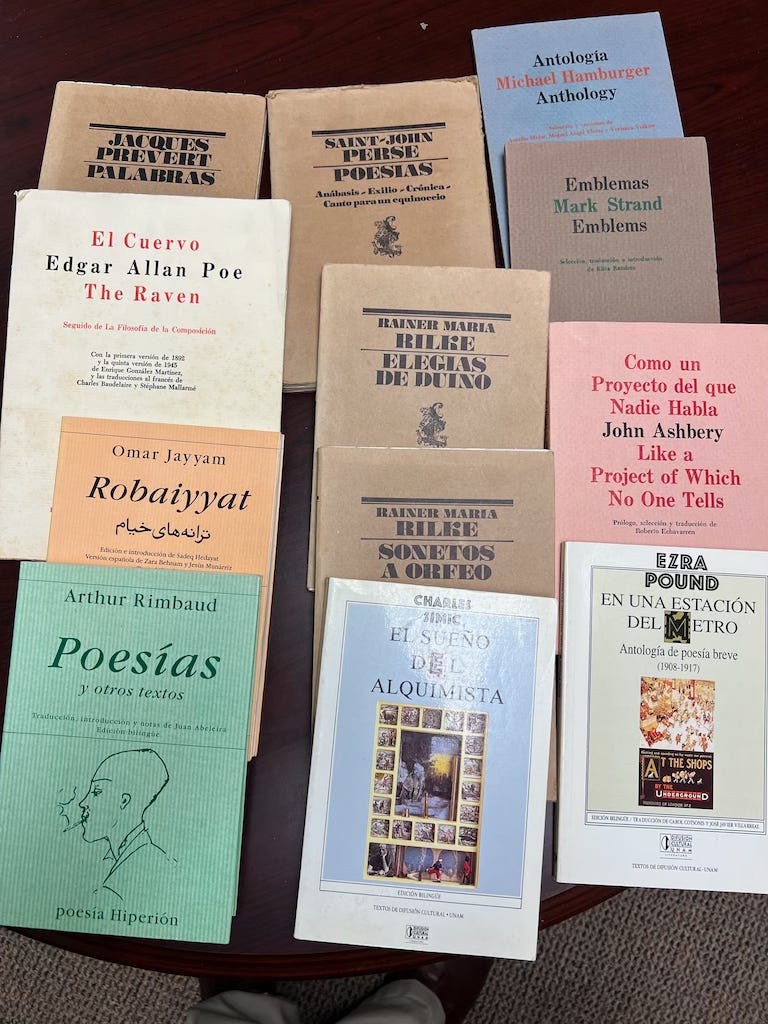

The closet, expectedly, has become storage for books, including the ones I had to move from Mexico after my mother’s passing and my collection of poetry. Because the closet was about to blow up in books, I have gradually been moving its contents to a storage facility. In the process, I have been encountering books that I bought while in college, with great financial sacrifice. In particular, I found poetry books, mostly bilingual, from series that were both alluringly beautiful and that often meant skipping a few meals in a month to buy them.

Today, I have the privilege, inconceivable to my younger self, of buying most books I want when I want them. “I see it, I like it, I want it, I get it,” as the great materialist thinker Ariana Grande puts it, is my book-buying praxis. I often wonder if I belong to one of the last generations of people who will own a library, when even the younger students with the privilege to build one seem deeply uninterested in books, or in historical depth, or in collecting. This my be less of a judgment on them—product of their vertiginous, hypermediated, presentist epoch—than a testament to my own obsolescence, more evident any my even more anachronistic collecting of movies in physical formats.

Collecting, though, provides a history to each book that exceeds the experience of reading it, powerful in itself. I remember hearing one of my professors in poetry class saying in snark that a lot of Mexican poets wanted to be Saint-John Perse when I did not know who Perse was in the first place. This led me to the chase of a bilingual edition by Enrique Moreno Castillo, a philologist and poet who embodies the kind of broad humanist I wanted to become at the time. Perse’s French was deeply challenging to the language skills I acquired in three years at the Alliance Française in Mexico City, which remain the cornerstone of the skills that allow me to read in the language even if my oral communication has afforded me a lot of judgmental looks in Paris. To find it, I had to go from Puebla, where my university was located, to a now-extinct bookstore called El Parnaso, a victim of gentrification in the center of Coyoacán. I vaguely remember that the Rilke books also came from the same purchase, given that El Parnaso organized books by press. I do remember though that I skipped comida, the main meal of the day in Mexico, for half of the days of a month to afford my poetry purchases that day.

I also remember my desire to collect the books from El Tucán de Virginia, a press that famously published (and was rumored to be funded by) the brother of then president Carlos Salinas de Gortari, Raúl, who had ambitions of being a poet before landing in prison for many years. Even if the story is true, there is no question that El Tucán de Virginia used whatever money it had in some of the finest editions out there, from bilingual editions of otherwise unavailable contemporary poets to deluxe editions of classics. My treasure from those years is an edition of Poe’s “The Raven” and his essay “The Philosophy of Composition,” featuring two translations by Enrique González Martínez, who contributed to the transition from modernismo to the avant-garde, as well as the French versions by Baudelaire and Mallarmé. I do not believe there is a comparable edition of Poe in English.

Tracking Tucán books was (and is) a substantive challenge and the collection I have gathered is the result of a dialectic between deliberate effort and cosmic chance. The ones shown in the photos result from the class of US literature I took and my later engagement with Harold Bloom’s work. I looked for The Raven feverishly during a trip to Mexico City and found it after six or seven bookstore stops. Not as expensive as the editions from Spain, the Tucán books were a less steep financial climb for my mom and me. Over time, I acquired the Michael Hamburger book, after being struck by the Spanish-language edition of The Truth of Poetry. Mark Strand was very well liked in Mexico due to his translations of poets into English, so Emblems was in the conversation. I owe my desire to purchase John Ashbery’s collection to Harold Bloom’s bombastic praise. The US poetry I read in those years, which includes the editions of Simic and Pound in UNAM, were deeply significant to my reading history.

The jewel of my collection are the handful of books from Poesía Hiperión. At the time, there were obscenely expensive imports, with a markup from their more affordable price in Spain. Excellent bilingual editions with philologically careful translations. There were many other editions of Arthur Rimbaud and Omar Khayyam, but I would have no other. The Rimbaud I purchased with a gift from my mom, who had to take a loan to celebrate my birthday. I do not know if she would have approved of the contents, her only reference to Rimbaud was the fact that Leonardo DiCaprio played him in Agnieszka Holland’s film Total Eclipse, which accounts his troubled personal and erotic relationship to Paul Verlaine.

I guess my interest in the sociology of literature was born out my keen economic awareness of the difficulties of buying a book, and of the sacrifices I decided to take to acquire the best edition possible. As I see the value of books to be scarce amongst my students and universities increasingly devaluing the wealth in literature, Going back to the memories of discovering these books, the sacrifices that I took to have them and the way they have accompanied me over decades reminds me why the humanities are worth fighting for.

I am closing 2024 shrouded in melancholy and resolve: melancholy for the constant loss of something that is so precious to me an d to the world and resolve to do my best to preserve it and pass it forward, even it if is a Sisyphean task. There is no wonder that the three last books of my year are about how literature, art and poetry resist the present. Melancholy may be a necessary affect for the fights to come in 2025.