This is the third and final entry of my favorite culture of 2024. My favorite music and my favorite films were shared in previous days.

The past year, I decided to return to reading in force. This meant to no longer allow the everyday duties of life and work to stand in the way of having proper reading time, and to maximize the opportunities to read. I did a lot of reading during travel and I no longer do anything on planes and trains but reading books. This was important because, as academia continues to feel increasingly uncomfortable for the humanities, reading is the constant reminder as to why I became as scholar in the first place. Even though there are days in which cinema is my favorite thing, literature is my first intellectual love and I returned to this love for books in full force.

Because of these efforts not only do I have a much bigger list than last year, but I also read far more books. The other thing that paid off was last year’s resolution to read more books in translation. There is an embarrassment of riches there that rarely makes it to list. If one just takes Dalkey Archive, Archipelago, New Directions, and Deep Vellum in English, and Impedimenta, Acantilado, and Galaxia Gutenberg in Spanish, one can last years reading amazing literature. This reorientation meant I wanted to read even more.

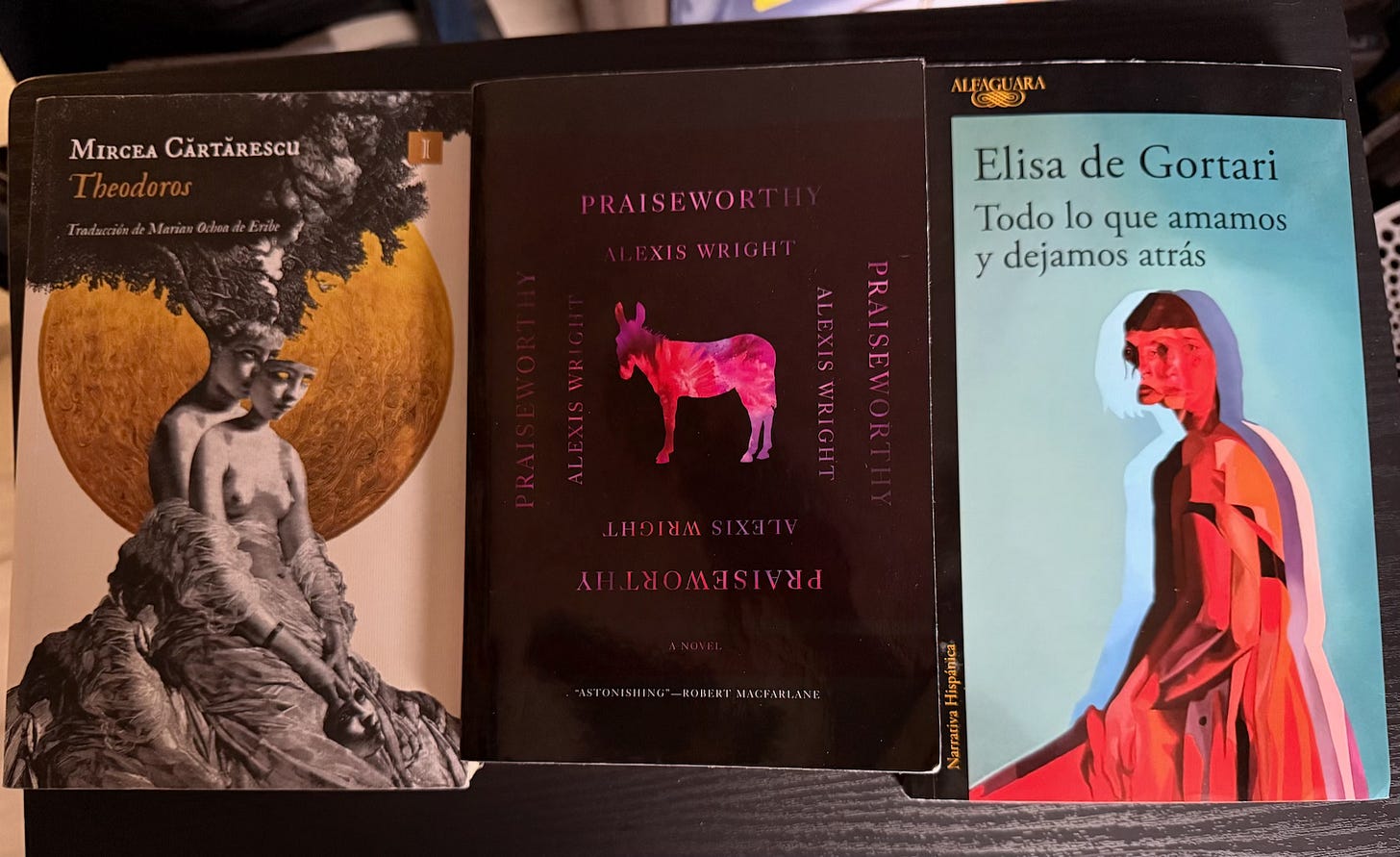

Paradoxically, my favorite book of the year was written originally in English, but it is from an aboriginal writer in Australia, Alexis Wright’s Praiseworthy. It really makes no sense to me that the Booker passed it over while shortlisting mediocrities like Creation Lake, the most overrated book of the year, or Samantha Harvey’s Orbital, a beautifully written but deeply uninteresting book.

As far as US fiction goes, I honestly did not like anything enough to make it to a top 25. But there was some good stuff including Greg Gerke’s On the Suavity of the Rock and Nora Lange’s US Fools, which I would recommend. I also celebrate that Percival Everett’s James, a fantastic novel by who may be the best US writer in production today, has gotten so much press, but the book kept sliding out of my favorites as I read works from elsewhere. It was also ridiculous that James was passed over for Orbital in the Booker. I do think the US does much better in poetry, and Danez Smith and Diane Seuss were a real joy to read.

In the end, I read 401 books in 2024 not counting re-reads, or books I read for research and teaching. Of these roughly 250 meet the criteria for the list. The list includes books published or translated for the first time to the language I read it between 2022 and 2024. I do not include classics, because I find it facetious to come out and say that the best book one read in a year is Don Quixote. At the end of this post, I will highlight a few books I enjoyed that do not meet my criteria.

It is sometimes difficult to make distinctions between the reading I do for this list and the reading I do for work, and some of the latter enter in the former. I would say at least seventy-five of the books within the 401 are Mexican literature, so there are a few in my list that may be off non-Mexicanist radars, but I stand by them as favorites. I think that I am a bit exhausted of the many books of autofiction and autotheory in Mexico, particularly those related to parents and children, a topic that is very uninteresting to me in general. Some of them are excellent, though. To people interested in that register, I strongly recommend Ave Barrera’s Notas al interior de una ballena, in my opinion the best entry in the genre this year, from one of Mexico’s most talented (and best kept secret) writers. But ultimately, I became more oriented towards books working strongly in fictionalization. Gabriela Damián Miravete’s book is earning universal acclaim deservedly. But I want to boost. Elisa de Gortari’s brilliant Todo lo que amamos y dejamos atrás, the best Mexican book I least last year. It is a very compelling and well-constructed speculative novel. I also want to boost Mikel Ruiz, a Maya Tsotsil novelist who has reached a high point with her rigorously written historical novel Los disfraces de la muerte.

In terms of academic books, I read a few that would qualify, but being embarked in finishing a few book projects between last year and next year, most of my academic reading is focused on research and teaching and thusly not eligible for the list. I did include a crossover collection, Revolution in 35 mm, in which a group of scholars and critics provide an introduction to global revolutionary cinema. It is comprehensive and very well done, and I hope it finds readers. I also found myself compelled by Anna Kornbluh’s bold Immediacy (who would not qualify anyways because she is a dear friend), and Nicholas Dames’s admirably erudite The Chapter, the kind of classic work of literary criticism I wish I was writing myself.

Finally, before dropping the list, books is the one department in which I could have conflicts of interest. Therefore I do not consider in the pool of 401 books any work by colleagues at my university or close friends. I also do not consider books for which I was an editor or a peer reviewer, or books that were gifted to me by the author. In these categories, I do want to recommend three books. My colleague Mona Kareem is a world-class poet writing in ARabic, and her book is a must-read: I Will Not Fold These Maps, translated by Sara Elkamel and published by The Poetry Translation Center. I also have the luxury to have the great poet Mary Jo Bang as a poet, and her book A Film in Which I Play Everyone, published by Graywolf, shows her at the top of her game. And I received as a gift from the author Marina Azahua’s Archivo Agonía, published by Sexto Piso, an experimental novel written with significant self-imposed constraints that is very worth reading.

With all these clarifications out of the way, this is the list of my favorite twenty-five books. My favorite five are marked with an asterisk. They are organized by language (English, Spanish, Portuguese), with each of the three alphabetized by author last name. It includes two books (Couto and Balle) that I began reading in 2024 but finished in the very first days of 2025. I offer a bit more commentary after.

1. Michal Ajvaz. Journey to the South. Trans. Andrew Oakland. Dalkey Archive.

2. Linnea Axelsson. Aednan. An Epic. Trans. Saskia Vogel. Knopf.

3. Solvej Balle. On the Calculation of Volume I and II. Trans. Barbara J. Haveland. New Directions.

4. Dionne Brand. Salvage. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

5. Bei Dao. Sidetracks. Trans. Jeffrey Yang. New Directions.

6. Andrew Deigan and Samm Nette. Revolution in 35 mm. Political Violence and Resistance in Cinema from the Arthouse to the Grindhouse, 1960–1990. PM Press.

7. Isabella Hammad. Recognizing the Stranger. On Palestine and Narrative. Black Cat.

8. Iman Mersal. Traces of Enayat. Trans. Robin Moger. Transit Books.

9. Otohiko Kaga. Marshland. Trans. Albert Novick. Dalkey Archive.

10. Elias Khouri. Children of the Ghetto, Star of the Sea. Trans. Humphrey Davies. Archipelago.

11. Esther Kinsky. Seeing Further. Trans. Caroline Schmidt. NYRB Books.

12. Peter Nadas. The Shimmering Light. 2 volumes. Trans. Judith Sollosy. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

13. Saneh Sangsuk. The Understory. Trans. Mui Poopoksakul. Deep Vellum.

14. Diane Seuss. Modern Poetry. Graywolf.

15. Danez Smith. Bluff. Graywolf.

16. Vanessa Angélica Villarreal. Magical/Realism. Essays on Music, Memory, Fantasy and Borders. Tiny Reparations Books.

17. Alexis Wright. Praiseworthy. New Directions. *

18. Gabriela Cabezón Cámara. Las niñas del naranjel. Random House

19. Mircea Cartarescu. Theodoros. Trans. Marian Ochoa de Iribe. Impedimenta.*

20. Gabriela Damián Miravete. La canción detrás de todas las cosas. Elefanta (First edition in Odo).

21. Phoebe Giannisi. Homérica. Trans. Vicente Fernández González and Ionna Nicolaidou. Vaso Roto.

22. Elisa de Gortari. Todo lo que amamos y dejamos atrás. Alfaguara. *

23. Antonio Moresco. Los comienzos. Trans. Miguel Ros. Impedimenta.*

24. Mikel Ruiz. Los disfraces de la Muerte. Fondo de Cultura Económica.

25. Mia Couto. A Cegueira do Rio. Companhia das Letras. *

As far as the books of fiction go, there is a trend here. I really got into books, many of them sprawling, that were engaged in interesting ways of dealing with historical and community memory, while also reflecting on the pitfalls of narrative. This is not new, in a way a lot of the books in this list derive from Borges and García Márquez in significant ways. Which is a way of saying that these books are returning to late 20th century forms of fictionalization. To me, they are more compelling books than a lot else being written today, which leads me to believe that the narrative modes that we identified with insufficient categories such as “magical realism,” and “postmodernism” are making an comeback, exceeding the principles that were discussed through theorizations are mostly exhausted..

That I gravitated towards these books is surprising to me because I tend to like stuff that bounds the narrative with the essayistic (like my favorite book of last year, Biography of X, which nevertheless is also a book that would be in the edges of this.m year’s genre inclination). But I really admired the scale and ambition of these works and the way they used literature to illuminate their various objects. My number one book, Praiseworthy, is ostensibly a novel centered on a government policy that created a lot of harm on the aboriginal population of Australia, under the premise of a supposed epidemic of child abuse. Instead of creating a realist or an autofictional work to engage with this problem, Wrigth imagines an allegorical family of characters whose subjectivity is destroyed by some version of this reality, veering into a madness that is nevertheless quotidian. All this while shrouded in an ecological disaster. The novel’s narrators are oracles, a gesture that could have been gimmicky, but in here it is perfect. I think its may be the best novel I have read in the decade so far.

My third favorite novel, Elisa de Gortari’s, works on a similar dystopian essay but projected towards the future, a society in which the Earth has acquired Saturnian rings, and an ensuing ecological disaster follows. In this case the narrator hovers around the figure of a journalist, but there is also a collective voice in the novel. I really hope translators and agents are jumping to publishing it in other languages.

Another version of this method of narration comes from the Romanian novelist Mircea Cartarescu. His Theodoros is my second book. I cannot describe who the narrator is without spoiling the novel, so I will just simply say that its mixture between epic and collective narrative is tremendous. And the history it tells is equally fascinating, a fictionalization built on a historical character from Romania who went on to become a ruler in Coptic Ethiopia. The kind of imaginative stuff I have been craving. Cartarescu is immensely popular in Spanish, which is a tribute to his translator Marian Ochoa de Iribe and the support of Impedimenta. But it is also because his work derives from a mixture of an openly Borgesian and Cortazarian roots in dialogue with the longstanding Rabelaisian tradition of eschatological and satirical fiction in Central and Eastern Europe, including writers like Milan Kundera, also deeply popular in Spanish. Theodoros is currently being translated by the great Sean Cotter and I look forward to its publication in English.

My fourth favorite book is Mia Couto’s A cegueira do rio, which tells the story of a massacre occurred in the borders between the German and the Portuguese colonies in Mozambique. It is told in fluctuations between a narrative voice that follows the perspective of various characters with first-person testimonials by the same characters told either retrospectively or posthumously. Couto is one of my favorite writers and I have been rereading his magnificent work after he received the FIL Prize for Romance-language writers in Mexico this year. He has not been as popular in English even after receiving the Neustadt Prize. But I hope my English-speaking friends will consider reading his masterpiece, Sleepwalking Land.

There are two more books in my longlist that could have easily been in the main list in another day that I still recommend in this mode: Geetanjali Shree’s Tomb of Sand and Vera Muftachieva’s The Case of Cem, which is also a classic.

Within this mode of narration, I would also note The Understory by Saneh Sangsuk, a Thai writer, a book that departs from the return of a woman from the grave. It is very unique and special.

Michal Ajvaz, a Czech writer who also happens to be a scholar of Borges and Derrida, provides a wonderfully sprawling novel in Journey through the South, where the influence of these two authors is very palpable.

On the extremes of the Borgesian spectrum, the first two volumes (out of seven) of Solveij Balle’s On the Calculation of Volume are masterful. They are the diary of a woman living the same day over and over, and each chapter is a diary entry numbered after the number of days in which the same has repeated. It is the kind of narrative premise that would be a trap in lesser hands, but works beautifully here. I look forward to the next volumes.

My fifth favorite book, Antonio Moresco’s Los comienzos, the first of a trilogy whose full translation to English and Spanish is in progress, is also a Borgesian book, full of intellectual ambition and wonder. I do not dare to describe it in short, but it really pays off to read it.

A unique book is Aednan, a marvelous epic in verse by the Sami poet Linnea Axelsson, on the long history of dispossession and resistance of indigenous Laplanders in Scandinavia. I never thought I would read a book like this, we need more epic poetry in our lives. Although it belongs more between the narrative works, it is also my favorite work of poetry this year.

An oddball book in this list is Esther Kinsky’s Seeing Further, a novel about a woman that buys and restores a movie theater in the border between Hungary and Romania. It’s mostly a novel for cinephiles, but raises beautifully questions of memory and cultural loss.

The question of history is also deeply present in these books. Besides Couto, Gabriela Cabezón Cámara wrote in Las niñas del naranjel a reconsideration of Catalina de Eraúso which is also a reflection on questions of colonialism. It my favorite book from South America (and the only one to make it to the list in the end, which is in part a factor of me getting books belatedly).

I did like Mónica Ojeda’s Chamanes eléctricos en la tierra del sol, her best book, but I would be remiss to not mention that it is currently ensnared in a plagiarism accusation for which I have no elements of judging, but that at the very least is raising questions of who is visible and of appropriation.

Also in my shortlist are Gabriela Wiener’s Atusparia, not as great as Huaco retrato but definitely a worthwhile read, Cynthia Rimsky’s Clara y confusa, a very skilled novel about class and love, and Diego Recoba’s El cielo visible, a very good and ambitious novel that did not rise as a favorite because there is a little bit too much Bolaño in it for my taste.

As far as Spain goes, I read with great admiration Sara Barquinero’s Los escorpiones, which carries strong influence from David Foster Wallace and Thomas Pynchon, unusual in Spanish, but the novel is overambitious and does not always sustain those ambitions. I would love to read whatever she writes next.

On a more political inclination, I would like to recognize Otihiko Kaga’s Marshland, a tremendously rich novel about the experience political repression and unjust incarceration. It is winding and repetitious and something readers of Knausgard may enjoy, although it has more opening political themes. Not a top favorite because it is a bit of a punishing read, but it pays off for persistent readers.

One cannot speak of the pain of history and the present without attention to the genocide in Gaza, and the longstanding plight of Palestinians, which is at the center of many literary considerations. I really loved the second volume of Elias Khoury’s trilogy Children of the Ghetto, which is centered on a Palestinian man born in the year of the Naqba. It is a novel on the question of death, erasure and identity that follows Khoury’s masterworks, and reading him is a tribute given his recent passing.

The question of Palestine also brings me to my favorite essay of the year, Isabella Hammad’s Recognizing the Stranger, which gathers two texts, respectively written before and after the October 7 attack by Hamas. She is the author of two immensely good novels, and reading her talking about the ethics, possibilities and limites of fiction, and on the relationship between literature and Palestine is riveting.

Also in the essay category, Iman Mersal’s Traces of Enayat is a very compelling essay about researching the life and erasure of Egyptian writers Enayat al-Zayyat, who took her own life at age 27 after publishing a novel. It is a great exploration of canonicity, cultural memory and gender.

The other two essays that made it to my favorites also touch on the question of the ethics of literature. Dionne Brand’s Salvage is a brilliant reflection on how to reckon as readers with literary classics wrapped with histories of colonialism and racism.

Vanessa Angélica Villareal, also a fantastic poet, delivers in Magical/Realism a wonderful, personal reflection about culture, violence and healing.

Breaking the exception against my resistance to autofictionalization, I did love Peter Nadas’s two-volume, 1200-page memoir Shimmering Light, which meanderingly depicts the history of his family using the Freudian method of dream interpretation. It is a real time investment and tough to get into, but it flows great once you get in the rhythm. I devoured it in a flight to Europe this fall.

Poetry was not in top of my list which means I should probably seek more of it. But I read many great books. I was into reading modern and contemporary Greek poetry this year and besides reading a lot of Elytis and Ritsos, I picked up the works of Phoebe Giannisi. I loved her collection Homérica in Spanish, which ties more clearly to the mainstream of Greek poetry. The book is also available in English. Her book Chimera, available in English, is more wonky, and not quite a favorite of mine, but pretty fascinating.

Diane Seuss and Danez Smith’s books can be read as a yin and yang of the same question: the limits and possibility of poetry. They both have different answers that I prefer not to spoil, but different as they are, I contend that reading them together is quite illuminating.

Thinking about some of the same questions, a favorite, Bei Dao, delivered this year a long poem of many cantos, that reflects on the life of the poet, and the influences in his writing. A real beauty.

Beyond the list, here are some books that do not qualify for it, but that I recommend: Nina Yargekov, a novel about an amnesiac woman who decides to pursue a Cartesian method to recover her thoughts; Bouamel Sansal’s 2084, another bold book of speculative fiction and collective narrative; and Gerard Murnane’s Inland, which really blew my mind.

When I was tallying this list, I realized I barely read classics this year, which is a bad habit, especially because I have become allergic to this oblivion of the past that results from the gutting of the humanities. So my new year’s resolution is to read less unremarkable contemporary books and read more classics, whether for the first time or reread after many years. I am already salivating for the new Acantilado translations of Rabelais and Tasso into Spanish, and the books by Goethe and Samuel Johnson I bought for this purpose. Next year’s post will report on this.

In the meantime, I hope you found a song, an album, a film or a book that will mean something to you in my lists. Thanks for reading and for your generous interest in this newsletter. I promise I will not neglect it in 2025.