My Favorite Books of 2023 (Part two of four recaps)

There was a lot I read and liked this year, but only a small handful of recent books stayed with me enough to call them favorites.

This is the second recap of the year. My favorite music of 2023 was the first. You can expect the following two before January 15.

When I think of my favorite books every year, I face a challenge. I read a lot of them, trying to keep up with the books of the past two years as best I can. Because of this, there are a lot of works I really like when I read them, but they fail to linger as I move on to other readings. There are times when I was sure a book was going to make it into my favorites, and then, as I reflect on the previous year, I realize that my enthusiasm weakened somewhat. It is entirely possible that some of the book in this list will not be as meaningful to me in the long term, which is hard to predict. And yet, because I have read so much, my standards for favorites have gotten tougher over time and I struggle to name more than a few books every year. This year, I decided to keep it at eleven, paring down an original list of fifteen, because, in all honestly, the four that I removed right before writing this post are not as good or significant to me as the ones that survived reconsideration.

My rules for the list are as follows: works published in the language in which I read them in between 2021 and 2023, which I read in 2023 for the first time. Because it sometimes takes more time to reach books in translation, only two reached this list, but to be honest there are a few others that people really loved and I did not. I also find it facetious and silly when someone is asked about the books the year and they answer with Don Quixote or something like that, because it entails an unwillingness to take risks on the durability of books that have yet to pass the ruthless filters of canonicity. Which is why I do not include here a book I loved, Emily Wilson’s translation of The Iliad, since it does not belong to the same set under comparison here.

I exclude from this list books for which my liking may be informed in part by some form of conflict of interest. I therefore do not list books by my closest friends and collaborators, by colleagues from my university colleagues or my mentors. Of course, I would never put here books from the series I edit. I will discuss those on the fourth recap, dedicated to my publications. I do not include books that I read for work or for teaching. I will recommend from the books disqualified my colleague Martin Riker’s novel The Guest Lecture, which is a masterclass in the narration of inner consciousness and time, as well as one of the best novelizations of economics I have read.

I read a lot of translations and I always advocate for reading the extent of the world, but in many cases translated books reach me too late to make it to the yearly list. I am a bit troubled that so many books coming from the US are among my favorites of the year, because I sincerely do not believe the US is where the best literature in the world is coming, but proximity can be an unavoidable curse.

I did spend some time reading works that failed to elicit the kind of intense engagement required to be in my favorites. I am very happy that Jon Fosse got the Nobel and I think he is objectively one of the best living writers in the world. But spirituality leaves me cold, and his books are a little too full of illumination for my taste. I do not see why people loved Maylis de Kerangal’s Eastbound so much, it felt pretty average to me. I also read underwhelming books by writers I love, like Cees Nooteboom, Roberto Calasso, Scholastique Mukasonga, Marie N’Diaye and Laszlo Krashnahorkai. And some of the authors who were real discoveries to me this year, like the Romanian Gabriela Ademesteanu or the Palestinian Adania Shibli, did not meet my temporal criteria.

The book in translation I loved the most this year was Delphine de Vigan’s Based on a True Story, which is a masterclass in suspense writing, more mind-blowing because it is in fact also an autofictional work about the writing of the book itself. To me the best autofiction in the world comes from the great quintet out of France—Angot, Carrère. De Vigan, Ernaux, Louis. The Anglophone counterparts do not even come close. I also found Adania Shibli’s Minor Detail to be brutally relevant given the current war on Gazans, and I regret learning about it after the censorship of the author in Germany, rather than reading it when released. There is no question that this is a book that must be read by everyone who wants to understand the Palestinian perspective with humanity and historical depth. The two books I read by Ademesteanu, The Encounter, translated by Alistair Ian Blyth, and Vidas provisionales, translated by Marian Ochoa de Eribe, are extraordinary, and she should join Cartarescu as one of the Romanian writers with a global readership.

In any case, the only book in translation that makes it to my list because it meets my criteria is Édouard Louis’s powerful autofiction, which in part is an echo of my readings of Annie Ernaux last year. Louis comes from the same Bourdieusian engagement with gender and class but he is less clinical and more interested in conveying the question of emotional pain than Ernaux, his mentor and close collaborator.

There are only two books originally written in Spanish in my list. I found a lot of the literature I read in my first language less interesting. I liked a lot of books, but it felt I was reading them more as an assignment than for my own enjoyment or enlightening. Many of them are excellent but I doubt I would have read them without feeling a sense of obligation. Having said this, that so many of my favorite books this year came from the US makes me more determined to privilege translations and books from Hispanophone countries beyond Mexico in 2024.

I love literature more than I love scholarship (sorry, I know this may be controversial to many friends of mine), so a book of scholarship will rarely make it to this list. The only books by authors who are not primarily a literary writer in this list is Gabriel Catren’s Pleromatica, a book of philosophy that blew my mind and I keep thinking about. Even more notably, Christina Sharpe’s Ordinary Notes is the kind of masterpiece that anyone who has done academic work should aspire to write. It is unquestionably the best book of nonfiction I read all year.

But I do read a lot of books by academics and I am always willing to recommend them. Masha Salazkina’s World Socialist Cinema was the best scholarly book I read this year (a short note of mine on this book will be published very soon). I also enjoyed reading Mark McGurl’s Everything and Less and Dan Sinykin’s Big Fiction. I have objections to both, mostly stemming from their US-centricity, but they are really excellent works of literary sociology. I am also a sucker for books about the trade of criticism, and I really enjoyed my internal debates, agreements and disagreements with Jonathan Kramnick’s Criticism and Truth and A.V. Marraccini’s We the Parasites. But, quite frankly, my enjoyment of and engagement with the top ten books in my list below is even deeper.

I usually do not like nonfictional books aimed at the trade market, but there are three here that I found both lucid and exceptionally well written. Myriam Gurba and Héctor Tobar published books that confirm my sense that they are two of the most impressive US LatinX writers. Creep is a collection of essays in which Gurba writes with great bravery and intelligence. What I like the most is that her writing refuses to play to the stereotypical minority-writer tropes that satisfy the mainstream of the American book market, and instead opts to confronts readers with the unvarnished consequences of everyday violences. Tobar put in his book a lot of the ideas I often struggle to articulate when thinking about the minoritization of Latines and Latin Americans, and, particularly, the flattening of our multinational, multirracial, class-diverse, immigration-status-diverse communities into a homogeneous box to become digestible to the US regime of racial classification and segregation.

Reading poetry is very important to me, but it was not a great year in books that lingered with me. The only representative the genre in my list is Andrea Alzati’s collection Recen por mí, which is fantastic, but I am also fond of it because its publication coincided with me purchasing one of her artworks. I really need to spend more time looking for great poetry books next year. In Mexico they can be extremely hard to find, and in the US there is such an ocean of them that it is hard to pick out the truly great ones. To be fair, there is a lot of books of poetry I liked but I struggled to bring one to the list over the works of prose I included this year.

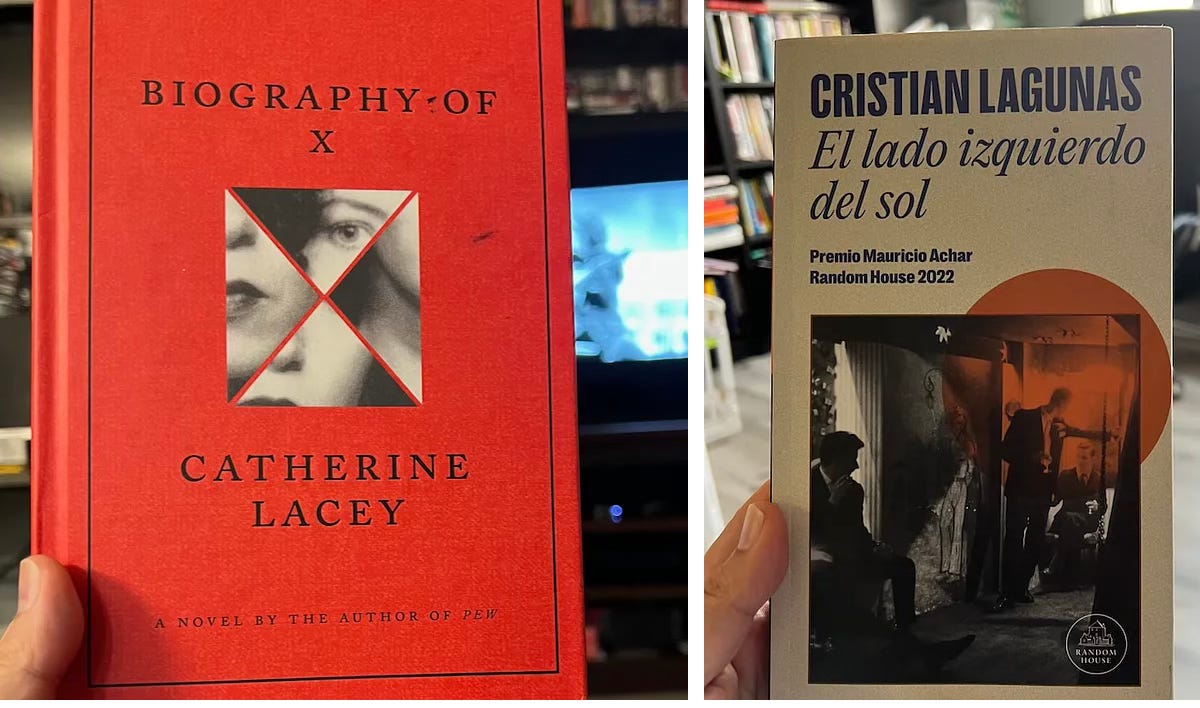

Of the books in my list, this year I have a clear winner, which is not usual. I absolutely adored Catherine Lacey’s Biography of X, which I read twice and about which I think a lot. I found it to be deeply inventive in its speculative work, bold in its use of documents and absolutely brilliant in its fictional deconstruction of the narrative structures of the non-fictional. My second favorite book was Cristian Lagunas’s powerhouse novelization of Yukio Mishima, El lado oscuro del sol, which I hope gets picked up very soon by an English-language publisher. I am partial to books that opt for cosmopolitan engagement instead of the comfort zones of the immediate, and Lagunas’s novel is one of the best books in Mexico’s cosmopolitan vein in years. The other novel that really blew me away was Justin Torres’s Blackouts, not only because of its masterful construction, citing Puig and Rulfo, but also because off its own use of the documental in fiction, a trait it shares with Biography of X.

Two more novels are a step below for me, but they are exceptionally good, even if I do not believe they got the press they deserved. One is C. Pam Zhang’s The Land of Milk and Honey, attractive to me due to the brilliance of its writing about food and the originality of doing food writing of such quality in a very well constructed apocalyptic fiction. The other one is Isabella Hammad’s Enter Ghost, a riveting narrative centered on a production of Hamlet in the Occupied Territories. It is not quite as good as her masterpiece and opera prima The Parisian, but there is no question that Enter Ghost is the work of one of the greatest novelists of our time. This is yet another book that tackles the Palestinian experience and the contrasts and conflicts with Israel with intelligence, depth and care.

Here is my full top eleven, organized by the last name of the author. I hope you find in this list a book that will be meaningful to you.

Andrea Alzati. Recen por mí.

Gabriel Catren. Pleromática or Elsinore’s Trance. Trans. Thomas Murphy.

Cristian Lagunas. El lado izquierdo del sol.

Myriam Gurba. Creep.

Isabella Hammad. Enter Ghost.

Catherine Lacey. The Biography of X.

Édouard Louis. A Woman’s Battles and Transformations. Trans. Tash Aw.

Christina Sharpe. Ordinary Notes.

Héctor Tobar. Our Migrant Souls.

Justin Torres. Blackouts.

C. Pam Zhang. The Land of Milk and Honey.